There is a common debate that concerns whether inequality actually matters. The argument for why inequality doesn’t matter is generally justified on the basis that, as long as everyone in a society has a minimum standard of living, it doesn’t matter if some individuals are extremely wealthy while others are making it by decently but without any cool luxuries. Thus, it is not inequality that matters, but poverty.

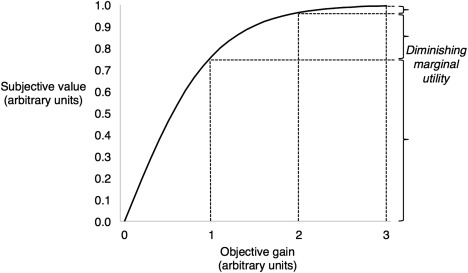

However, there are two common theoretical counters to the idea that inequality qua inequality doesn’t matter. The first appeals to the concept of diminishing marginal utility of income. This is the notion that an extra dollar in the hands of someone who is relatively poor will benefit the recipient more than an extra dollar in the hands of someone who is relatively wealthy. In mathematical terms, the link between income and utility is positive and concave:

If this is the case, then a redistribution of income from a more well-off person to a less well-off person will raise total “utility” or “happiness”, even if both people are at or above a baseline quality standard of living.

The second theoretical counterargument concerns how humans naturally respond to inequality. While certain relations between individuals are not necessarily zero-sum (voluntary transactions, for instance, are commonly used as examples), others are. Status is one of them. People naturally look at inequalities between themselves in terms of status markers such as wealth and popularity, and can become resentful of them.

A simple illustration of this can be seen in behavioral economics research with game theory. The ultimatum game is a simple two-player game in which one player serves as the “proposer” and the other as the “responder”. The proposer decides how to split $10 (usually) between them and the responder. The proposer can offer the responder all of the money, half of the money, none of the money, or any other combination. Once the proposer has made their offer, the responder can accept or reject it. If the responder accepts the offer, they walk away with their share of the money. However, if the responder rejects the offer, neither party gets anything.

If the responder were completely unconcerned with inequality and only concerned with how much money they personally received, they would accept any split that gave them more than $0 and be indifferent between accepting and rejecting an offer in which the proposer received all the money. Experiments show that individuals will, in many cases, reject unequal offers, even if they make some money by accepting them. In other words, they will actively harm themselves to spite another person over an unequal deal.

This “inequality aversion” dates back millions of years in our evolutionary lineage and is evident in other species related to us. A particularly fascinating instance of this is shown in the following TED talk, where an experimenter had two capuchin monkeys do the same task for a reward:

Here, for the identical task, one monkey was rewarded with cucumber, while the other monkey was rewarded with a grape. Monkeys consider grapes a much better reward than cucumber, which created a subjective sense of inequality between the two monkeys in terms of how they were treated. The monkey, rewarded with cucumber, became increasingly agitated over the pay inequality, ultimately rejecting it and throwing the cucumber at the experimenter. Once again, this is an instance where an individual is willing to harm themselves – in this case by not eating food given to them and throwing it instead – out of spite for whoever is perpetuating the inequality – in this case the experimenter.

So there are theoretical reasons to believe that inequality may still be harmful for a human society even if everyone is well-off. If individuals are naturally resentful of inequality or are still indirectly harmed by the effects of diminishing marginal utility, this may imply that the presence of inequality itself could carry social problems, such as lower subjective well-being, lower social cohesion, or even higher crime. But do these links actually bear out?

When examining the link between inequality and crime or social cohesion, research suggests that income inequality is associated with increased crime and decreased social trust. However, several studies have found that the actual poverty rate accounts for the entirety of this effect, at least on crime. Pridemore (2008) and Pare & Felson (2014) both found that after controlling for poverty, inequality was unrelated to crime, whether measured by homicide, assault, robbery, burglary, or theft.

In fact, Durante (2012) found that, when examining the link between inequality and crime in the United States across 1981-1999, after controlling for poverty and unemployment, the relationship was negative. In other words, higher income inequality actually predicted lower crime rates, whether property or violent.

While I am not aware of any research examining inequality and social cohesion while controlling for the poverty rate, the most parsimonious explanation is that societal-level inequality, in itself, doesn’t produce substantial negative social externalities. This would imply that inequality in itself probably has no significant adverse effect on social cohesion.

What about subjective well-being? A recent study by Sommet et al. (2025) conducted a meta-analysis of 168 studies. They found that individuals in more unequal areas do not report lower subjective well-being. While inequality was initially associated with lower mental health, once publication bias was corrected for, the association disappeared. Thus, it appears that inequality doesn’t actually matter in terms of the well-being of people.

Even in terms of political representation, there is little strong evidence that inequality matters. The sociologist Tibor Rutar reviewed research examining whether inequality undermines democracy and found that the empirical evidence for this claim is weak. In fact, it may be that inequality has no effect on promoting or undermining democracy. This suggests that at most, inequality has a small adverse effect on representativeness of a government, if at all.

An interesting thing to note is that people tend to have a very poor ability to perceive the actual extent of inequality in their society. When presented with diagrams referring to their country’s Gini coefficient, either measured by post-tax-and-transfer or pre-tax-and-transfer, individuals were only able to guess correctly at a rate slightly better than random. In fact, the correlation between changes in inequality across countries and people’s perceptions of changes in inequality is actually negative.

Political support for economic policies is also more related to perceived inequality than actual inequality. Support for redistribution was entirely unrelated to pre-tax or post-tax Gini coefficients of actual income at either the country or the individual level. However, perceived inequality was highly significantly related to both country and individual-level redistribution.

Similar effects were seen for perceived class conflict. There, post-tax inequality was significantly associated with greater reported tension between classes, whereas the impact of actual inequality was a third as large as that of perceived inequality. Furthermore, the impact of actual inequality disappears once controls for the country’s income and population are introduced.

Thus, while objective inequality may not matter, subjective inequality may. It is therefore arguably more important to try to eliminate perceptions of inequality than to actually eliminate inequality qua inequality.

But why do the theoretical arguments for why inequality matters not pan out when looking at the data? I think it comes down to two reasons.

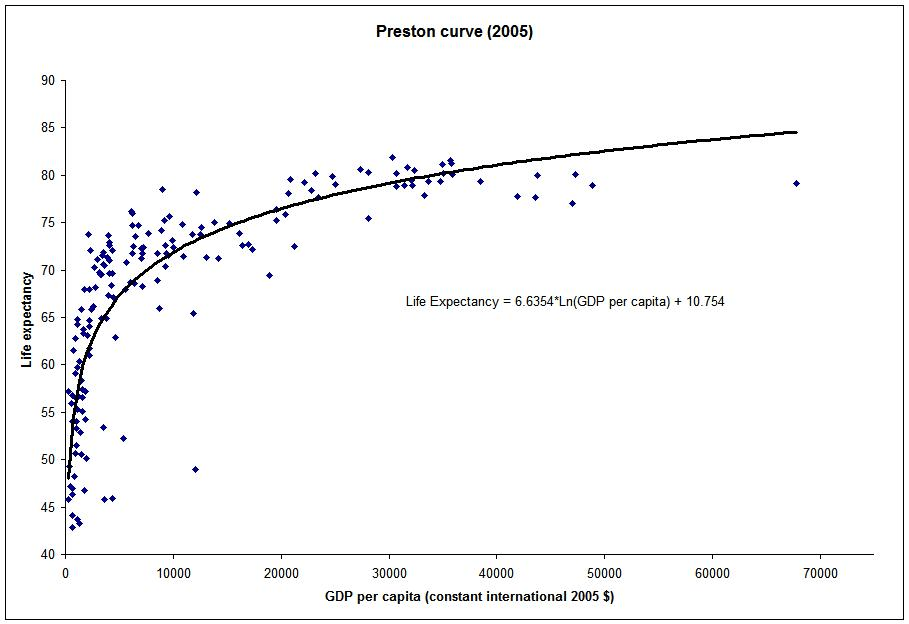

First, regarding the argument about diminishing marginal utility, while income does predict greater well-being, it only does so to a substantial degree up to a point. Past a GDP per capita of around $20,000-$30,000 a year, countries with higher income have essentially no difference in life expectancy, a relationship referred to as the “Preston Curve”:

The actual “utility” gains from additional income past that point may be so small that they are actually insignificant, even if a higher income before that point can predict greater well-being. Thus, inequality in high-income countries would not particularly matter.

Second, social resentment probably has more to do with subjective perceptions of inequality than with objective inequality. If subjective perceptions of inequality have nothing to do with actual inequality, there would be no strong relationship between inequality and proxies for social resentment, such as crime or social trust.

A lot of politics nowadays revolves around inequality, particularly economic inequality. Inequality between individuals and between groups is seen as something manufactured and intrinsically immoral. However, while there are relatively strong theoretical reasons to believe that economic inequality is harmful, the actual evidence suggests that it is not particularly harmful in and of itself.

Instead of focusing on inequality per se, we should be focusing on whether everyone has a decent standard of living. A society where everyone is well-off but some have much more income than others is monumentally preferable to a society where everyone is equally poor.

Leave a comment